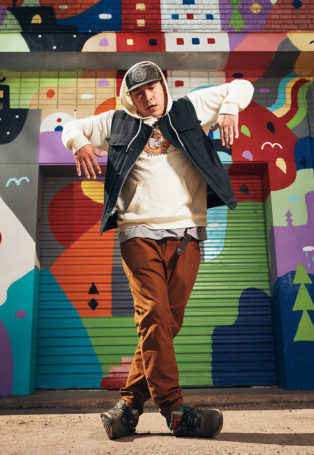

June 25, 2021

Twenty years after his first foray into Edmonton’s music and dance scenes, Matthew Wood continues to inspire collaboration — and community

Matthew Wood is a community centre. Ideas, people, art forms, cultures, subcultures, histories and futures: He is both a focal point and a staging ground for all of them. He opens his doors to the world that surrounds him, to every part of it, and transforms it into something that is both rooted and unimagined, a part of the whole that is pulling it somewhere new.

Wood is not easy to define, if only because definition by nature involves boundaries and restrictions. He performs under the name Creeasian, which nods both to his heritage — his father was Vietnamese and his mother Cree — and to his endlessly original approach to the mediums in which he’s most at home: dance and DJing. But it doesn’t quite capture the breadth and depth of his inspiration. Perhaps the most encompassing way to say it, is that he’s an artist. Still, if the purpose of an artist is to absorb the world and reflect back an entirely original perspective, he has made community-organizing as central to his practice as anything else.

“He rolled all the time with community — he always had people with him,” says Tim Hill, of Halluci Nation (formerly known as A Tribe Called Red), for whom Wood has been a touring dancer for more than six years. “The kind of aura he brings around, it’s always a very warm, light-hearted, inviting place. And he’s like that with everybody.”

“When he receives something, he always shares,” explains Gerry Morita, artistic director of Mile Zero Dance, who has worked with Wood for more than a decade, and recently welcomed him as an artistic associate at Mile Zero. “He’s a really strong mentor to other people, a teacher — he’s always bringing along youth or the community as a whole.”

If Wood’s place in the community has been recognized by his peers since shortly after he began dancing at community centres and at the Edmonton International Street Performers Festival nearly 20 years ago, it’s now also being acknowledged by the city’s institutions. This year has seen him recognized not only with funding from the Edmonton Artists’ Trust Fund but as the city’s Indigenous Artist-in-Residence. Whatever else it might mean, the implications for what it says about his place in the community are not lost on Wood.

“I always didn’t feel like I belonged everywhere. I always had to fight for my place to be, to prove that I belonged where I felt I belonged,” Wood explains of his youth, and the drive it gave him to create spaces where people could feel part of something. “I didn’t want to have that for people in my community. That’s always been the most important component for me. Because I didn’t want others to feel that same way.”

That spirit is as true in his extracurricular work as in his art. As the creator and driving force behind projects including downtown block party Cypher Wild and Sampler Cafe, which brings DJ equipment and know-how to communities that would otherwise never have access, Wood gives a platform and a place to truly “be” for people who are often overlooked, if not outright rejected, by too many in our city.

“As I was coming up, I would hear people talking about these things — like, ‘Downtown is an eyesore’,” Wood explains. “And I mean — I’m from there. I’m from these streets you speak of. You’re going to say that I’m a down- and-outer? How they going to say that about us?” For all that his organizing has done to smash perceptions and bring people together, the remarkable thing about Wood is that his performances radiate the same energy. As anyone who has seen him can attest, Wood is electric: blending influences that range from Cree syllabics to New York City b-boys, he is a beacon of pure charisma, a powerful light who draws in and energizes anyone who can see him.

As he begins another phase of his career, though, Wood is not content to rest on either his community work or his charisma. It’s clear from talking to him that he has taken this recognition to heart, and wants to use it, naturally, to bring more to his community; to help teach, to help expand the minds of people who are used to viewing his art and heritage through narrow lenses.

“When I first started getting into hip hop, at the time I didn’t know why I was drawn to it,” he explains. “But I understand now: it had the same energy as the powwows my mom would take me to. It wasn’t just about dancing — it’s about, ‘Why do you dance, what’s your story? What do you bring to the table?’ It’s about giving back, to the art and the community.”

To that end, he is using both the Trust Fund and his position as artist-in-residence to dive deeper into his Cree heritage, learning both the language and the syllabics, to better incorporate them into his art. Because, though a large part of his work until now has been about blending worlds — something he remains proud of, noting, “We do need to show that Indigenous people can exist in this modern world as modern” — he is also coming to appreciate how vital it is to provide a link to histories and traditions that were violently ripped away.

“I want to put these things into my art. Our art forms are all a form of prayer which leads back to our language: the beadwork, the sewing, the regalia; it all comes from the syllabics,” Wood explains. “I’m at the point — I don’t want to be the Indian in the cupboard, to just dance and get put back into the same place. So this is not just about creating art, it’s about bringing our origin stories, showing my community that everything we do is art.”

If that is a hefty responsibility for a guy who, he notes a bit acidly, has been too often dismissed as “the hippity-hopper,” he is not concerned.

“It doesn’t feel like a burden,” Wood beams. “In the Cree tradition, dancing is prayer. So, it’s something I’ve been praying for.”